By: Jazmine Sapenter-Coulter

In the study of African and African Diaspora histories, the interplay of voice and violence is a foundational theme that underscores the lived realities of Black women across the globe. African Studies, as an interdisciplinary field, offers a lens through which the struggles and triumphs of Black women can be understood not only in terms of resistance but also in terms of cultural survival and empowerment. Voice, in this context, is not just literal speech but a symbol of presence, agency, and power. Yet, throughout history, this voice has frequently been met with silencing violence—a mechanism of both colonial and patriarchal control. From the shores of West Africa to the Americas and the Caribbean, the tension between voice and violence reveals a deeper narrative of resilience and resistance central to Pan-Africanism.

Voice as Cultural Memory and Resistance

The concept of voice in African Studies encompasses oral traditions, storytelling, political activism, music, and more. Historically, African women have utilized voice as a method of preserving cultural memory and resisting oppression. Oral traditions such as praise poetry, folktales, and songs have been essential tools for transmitting knowledge, values, and resistance across generations. Women, as custodians of these traditions, have played a key role in maintaining the cultural fabric of African societies.

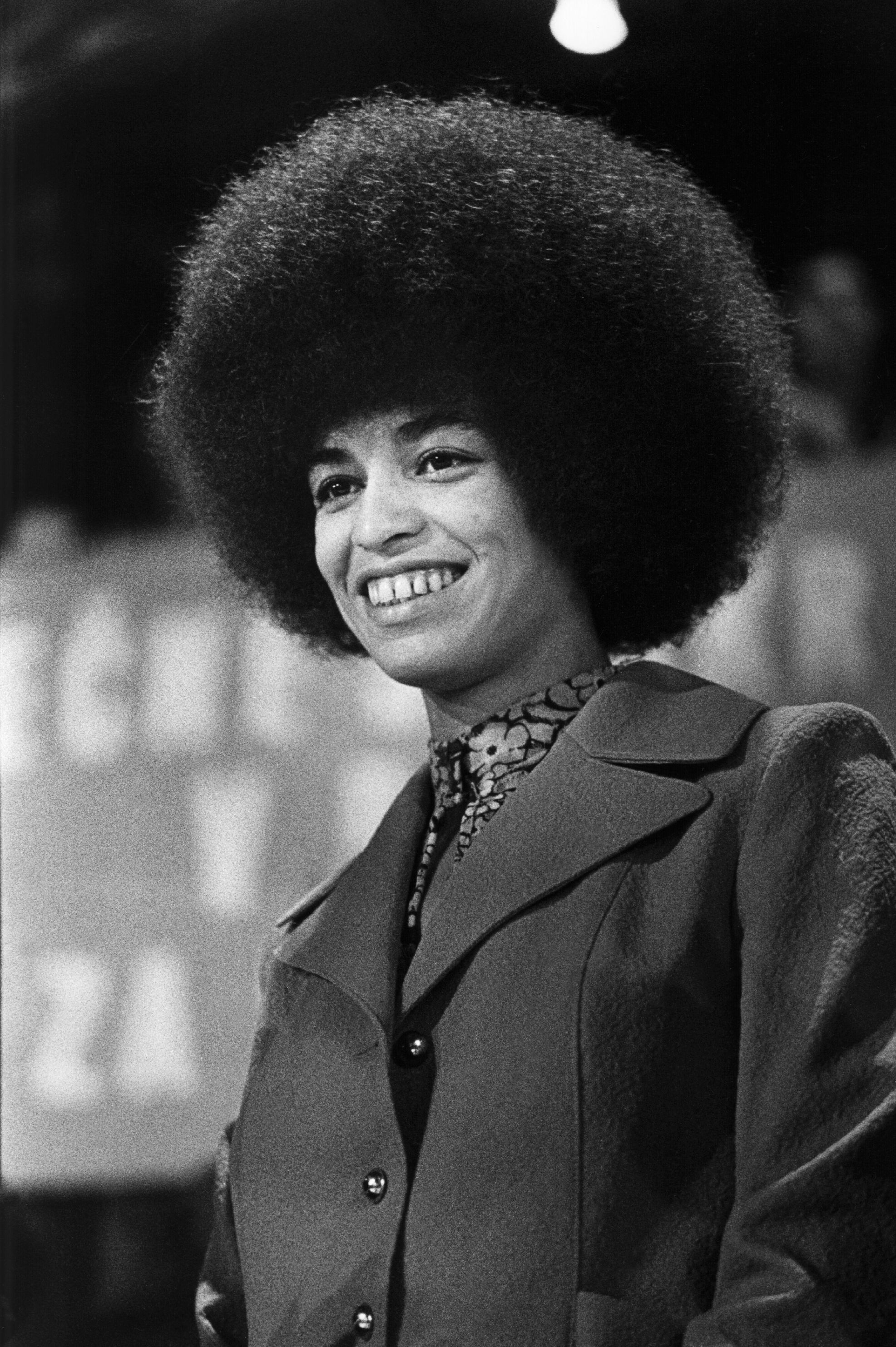

Pan-African thinkers such as Claudia Jones and Amy Ashwood Garvey recognized the power of voice in mobilizing communities and challenging colonial narratives. In modern times, voices of Black women activists like Winnie Mandela and Angela Davis echo these legacies, demonstrating how voice becomes a means of political empowerment and historical reclamation. Angela Davis has famously said, “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept” (Davis, 1989), emphasizing the transformative power of speech as action.

Voice, then, is not just about communication but about the assertion of humanity in the face of dehumanizing systems. It is about claiming space and refusing erasure—a theme echoed throughout African Studies, particularly in discussions of post-colonial identity and diasporic resistance. Saidiya Hartman, in her exploration of marginalized Black women’s lives, asserts, “The wild idea that animates this book is that young black women were radical thinkers who tirelessly imagined other ways to live” (Hartman, 2019), underscoring the urgency of vocal resistance and recovery.

Violence as a Silencing Mechanism

Colonialism, slavery, and racialized patriarchy have consistently used violence to silence Black women’s voices. This violence is multifaceted—physical, psychological, and structural. From the brutalities of the transatlantic slave trade to contemporary gender-based violence, Black women have endured systemic efforts to suppress their voices.

In many African societies, colonial powers imposed Western patriarchal structures that disrupted pre-existing gender dynamics and suppressed women’s roles in political and public life. In the diaspora, Black women have faced dual oppressions of racism and sexism. African Studies scholars like Amina Mama and Ifi Amadiume have emphasized how colonialism weaponized gender roles to marginalize African women and limit their societal influence. Amina Mama points out, “The greatest threat to women (and by extension humanity) is the growth and acceptance of a misogynistic, authoritarian, and violent culture of militarism” (Mama, 2003), revealing how violence extends beyond the physical into epistemic realms.

Modern manifestations of silencing violence include political exclusion, limited access to education, and the trivialization of Black women’s contributions in academic and activist spaces. Even within Pan-African movements, Black women’s voices have at times been pushed to the periphery, despite their critical roles in sustaining these movements. Frances Beal, in her landmark essay “Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female,” writes, “Unless women in any enslaved nation are completely liberated, the change cannot be really called a liberation” (Beal, 1970), emphasizing the compounded nature of racial and gender violence.

Pan-African Unity and the Centrality of Black Women’s Voices

Pan-Africanism, at its core, calls for the unity and solidarity of African-descended peoples worldwide. Yet, for this unity to be authentic and transformative, it must be inclusive of Black women’s voices and experiences. The work of Pan-African feminist scholars like Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí and Sylvia Tamale underscores the importance of integrating gender analysis into Pan-African discourse.

Black women’s voices are central to articulating the intersections of oppression that impact African and diasporic communities. From grassroots organizing to international advocacy, women have consistently been at the forefront of struggles for justice and equity. Movements like #BringBackOurGirls and #SayHerName highlight how Black women use voice to challenge violence and demand global accountability.

Jessica Horn argues that “African feminist thought arises out of lived realities and histories of struggle that are often misremembered or silenced” (Horn, 2015), reiterating the necessity of including Black women’s testimonies and strategies within the Pan-African canon. Keisha N. Blain also emphasizes that “Black women’s internationalism has always been rooted in a deep commitment to community and global justice” (Blain, 2018), reminding us that their activism transcends borders and must be acknowledged accordingly.

Moreover, cultural expression through literature, music, and visual arts provides a space for reclaiming narrative and affirming identity. African Studies recognizes these forms as vital contributions to the global understanding of Black life and liberation.

Conclusion

Within the field of African Studies, voice and violence are not isolated themes but interconnected elements that shape the historical and contemporary realities of Black women. Voice is an instrument of survival, resistance, and transformation. Violence, though pervasive, has never succeeded in fully silencing the enduring spirit of Black women across the African world. In honoring their voices within a Pan-African framework, we not only acknowledge their struggles but celebrate their indispensable role in the ongoing quest for liberation, justice, and unity.

References

- Beal, Frances M. “Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female.” In Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought, edited by Beverly Guy-Sheftall, New Press, 1995.

- Blain, Keisha N. Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

- Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge, 2000.

- Davis, Angela. Women, Culture & Politics. Vintage Books, 1989.

- Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. W. W. Norton & Company, 2019.

- hooks, bell. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. South End Press, 1981.

- Horn, Jessica. “The Power of Pan-African Feminism.” Black Women Radicals, 2015.

- Mama, Amina. “Sheroes and Villains: Conceptualizing Colonial and Contemporary Violence against Women in Africa.” Feminist Africa, no. 2, 2003.

- Amadiume, Ifi. Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society. Zed Books, 1987.

- Tamale, Sylvia. Decolonization and Afro-Feminism. Daraja Press, 2020.

- Patterson, Tiffany Ruby. “Diaspora, Pan-Africanism and the Global South.” The Black Scholar, vol. 33, no. 3-4, 2003, pp. 72-74.

- Oyěwùmí, Oyèrónkẹ́. The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses. University of Minnesota Press, 1997.