By Khalia Greer

To fully understand how theology functions as a key concept in Pan-African Studies, one must first define what theology is. Traditionally, theology is understood as the study of religious beliefs, particularly concerning the nature of divinity. It aims to develop a deeper understanding of God, scripture, and personal faith, all in pursuit of a more purposeful life. However, theology as an academic discipline was developed within predominantly white institutions, tailored to serve white communities. As a result, traditional theology failed to acknowledge or reflect the experiences, struggles, and spiritual perspectives of Black people. This lack of representation is what encouraged Black theologians to delve deeper into the concept and utilize unique Black experiences to pave a path so that future generations could look to a faith that recognized their ancestry and reaffirmed their identity.

Black Liberation Theology

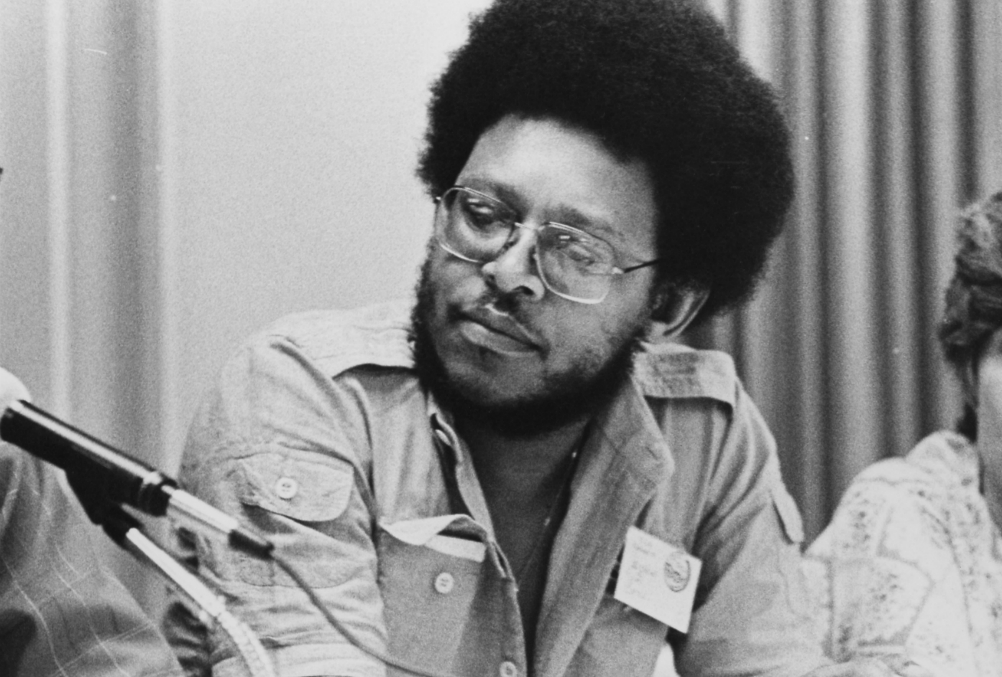

Dr. James H. Cone, the founder of Black Liberation Theology, personally experienced racism from white theologians and was one of the first individuals to criticize this blatant exclusion of the Black perspective and experience in traditional Christian theology, accusing them of moral evasion and theological apathy toward racial injustice. When this acquisition arose, white theologians rarely gave Cone a response, so Cone published his novel Black Theology and Black Power to challenge their silence. He explained that their silence stemmed from privilege because, “White theologians live in a society that is racist; the oppression of Black people does not occupy an important item on their theological agenda… Because white theologians are well-fed and speak for a people who control the means of production, the problem of hunger is not a theological issue for them“ (48). This confrontation continued throughout his life because, as a theologian himself, he refused to empathize with the white theologian’s flagrant neglect for the Black community. To Cone, they claimed to study a just and loving God but still chose to further condone the systemic suffering of Black communities, which was hypocritical.

In the 1960s and 70s, Black Liberation Theology gained momentum by focusing on the belief that God is at the forefront, aiding Black people through their struggle for freedom and justice. Cone emphasizes this belief even more in his novel Black Theology of Liberation. In his novel, Cone states that “God is Black” (73), not in a literal sense but symbolically, signifying God’s solidarity with those who suffer under racial oppression. He argued that any Christian theology that fails to side with the oppressed is not authentic and needs to be readvised. Cone also stressed that theological reflection must begin with an honest understanding of the Black experience. This radically reoriented theology from abstract doctrine to lived reality. The heart of Black Liberation Theology is to call individuals to action and instill the narrative that faith without a commitment to social change is ineffective. To Cone, theology is about more than just the study of religion; it is a way to transform the world by confronting racism and supporting the freedom and liberty of Black people and other suffering communities.

Womanist Theology

Building on this foundation, theologian Dr. Jacquelyn Grant, one of the founders of Womanist Theology, critiqued both Black Liberation Theology and white feminist theology for their failure to address the specific struggles of Black women. Grant argued, “In order for liberation theology to be faithful to itself, it must hear the critique coming to it from the perspective of the Black woman—perhaps the most oppressed of all the oppressed” (320). She noted that Black women were often left out of theological discourse entirely, stating that readers might assume either “(1) Black women have no place in the enterprise, or (2) Black men are capable of speaking for us” (322). Both assumptions, she insisted, are false.

Although the Black community as a whole has endured systemic racism, Grant emphasized that Black men have gradually been able to gain social and institutional power, while Black women continue to bear the compounded burdens of racial and gender oppression. It is not possible for the oppression of Black women to be considered and properly addressed in Black Theology if they were not involved in creating it; instead, it further condones the patriarchal structures and the condemnation that the liberation movement tried so hard to get away from. Grant also critiques white feminist theology, which often ignores the racial dimensions of Black women’s experiences. With that, the Womanist Theology founded by Katie G. Cannon, Jacquelyn Grant, and Delores Williams emerged as a corrective: a framework essentially created because Black women had enough of groups misrepresenting them and acting on their behalf. Womanist Theology is the powerful voice of Black women standing up and taking up space in a place that previously silenced them. By centralizing the complex intersectional experiences, perspectives, and concerns of Black women in the study of faith and the world, Womanist Theology was able to confront the ways that Black women have been made out to be invisible and emphasize lived experiences and resistance as resources of theological insight. Their work aims to rethink God and Christ in ways that respect the dignity of Black women, focusing on real-life experiences, storytelling, and a new idea of freedom, making sure that Black women’s voices are not only heard but also are the foundation for any future actions that promote liberation, thus ensuring that Womanist Theology remains an essential correction.

Conclusion

Theological movements, including Black Liberation Theology and Womanist Theology, continue to hold undeniable relevance for contemporary struggles for social justice, liberation, and the affirmation of Black spirituality and identity. These theologies created by Black scholars such as Dr. James H. Cone and Dr. Jacquelyn Grant have made way and reshaped the meaning of theology within Pan-African Studies, not as an abstract discipline but rather as a liberative force that is rooted in the experiences of the oppressed. By ensuring to center the voices of Black women and men, these movements were able to restructure God in terms of solidarity, affirming the Black community, and demanding social action in hopes for change. This created a path that allowed Black scholars to redefine the gospel message in a format that resonated with them on a more personal level and began bridging the gap between Black women and men so that as a collective they could claim a space in theology. Together they challenge the oppressive structures present in religious institutions and in society as a whole, insisting that true faith is supposed to be intertwined with justice. All in all, their theological developments are acts of both resistance and reclamation to self-determination and empower Black communities to know God for themselves and on their own terms.

Recommended Lectures

Works Cited

Cone, James H. God of the Oppressed. Orbis Books, 2020.

Cone, James H., and Cornel West. Black Theology and Black Power: 50th Anniversary

Edition. Orbis Books, 2019.

Cone, James H., and ʻĀmir ʻAbdullāh. A Black Theology of Liberation: 50th Anniversary

Edition. Edited by Peter J. Paris, HighBridge Audio, 2022.

Grant, Jacquelyn. “Black Theology and the Black Woman .” The New Press, New York,

New York, 1995, pp. 320–336.

Grant, Jacquelyn. “The Third Annual James Cone Lecture with Dr. Jacquelyn Grant.”

YouTube, YouTube, 12 Apr. 2023, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YfYBt-V-BM8.

Grant, Jacquelyn. White Women’s Christ and Black Women’s Jesus: Feminist Christology

and Womanist Response. Scholars Press, 1989.