By Jared Mabra

Meaning andOrigins

A term used by Black people in the francophone world to celebrate the Black Identity and Black Culture. The first time Négritude appeared is speculated to originate in the third issue of a Francophone Magazine dedicated to Black Culture and Black Identity in France and the French-speaking colonies in Africa and the Caribbean, L’Étudiant noir, published in 1935 by Aimé Césaire. Yet there hasn’t been any physical proof of this existing, and the only mentions of this happening come from Césaire in a 1940s interview about the word’s origins.

Influences

The first influence came from the US with the Harlem Renaissance and popular members of the movement, such as W.E.B. Du Bois’ Double-Consiousness from his book “The Souls of Black Folk”. Many Négritudists would be inspired by this concept to explore the French identity and how that conflicts with the African identity. Alain Locke was another big inspiration with his novel, “The New Negro” and the New Negro Movement that he created. Major goals that both the New Negro and the Negritude movement Because of Locke’s novel, The second influence would be from Black Jacobinism. A movement that originated from Haiti with Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Haitian Revolution.

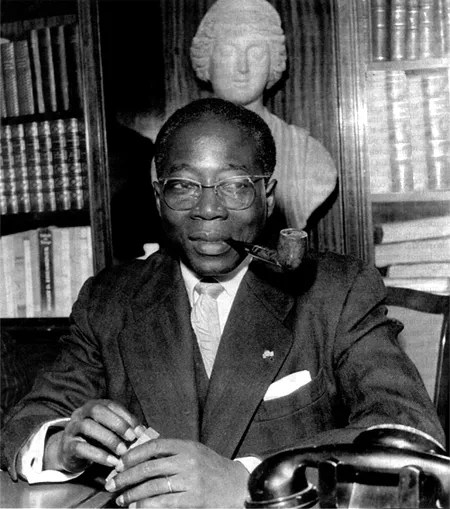

Founders of the Négritude movement

There are three main founders of the Négritude movement. Aimé Césaire is the man to officially coined the term in his masterwork, “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” or “Notebook of a Return to My Native Land, Return to My Native Land” published in August 1939. Leopold Senghor is the second figurehead of the movement that wrote “Anthology”, published in 1948, where he introduced Négritude to French intellectuals as an anti-racist movement to fight against colonialism in France. The other figurehead with less recognition is Leon Damas. He was an outspoken critic of what he described as the privileged Eurocentric epistemologies and methodologies that he believed were prevalent in Black studies.

Politics

Besides literature, Aimé Césaire and Leopold Senghor were also politicians who contributed to helping the French colonies with rights and legislative bills. Aimé became the deputy to the French National Assembly for Martinique from 1945 to 1993, with him getting the departmentalization Law that established Guadeloupe, Martinique, Réunion, and French Guiana as official French overseas departments instead of part of the French Colonial Empire. French laws and regulations now are extended to these 4 regions, unlike before, which had a different set of rules that would demoralize the civilians. The main goal of the departmentalization law was to make the people of these 4 colonies into full-fledged citizens instead of subjects of the French. Leopold Senghor was an advocate for Africans to have some form of assimilation into French culture and would push for French citizenship for all French territories. Later on, when Senegal won its independence in 1960 and was a part of the Mali Federation, he participated in their first election and became the first president of Senegal on the 5th of September.

Differences

With the Négritude movement, the main 2 goals were for the décolonisation and ré-Africanisation of the French colonies. yet each of the members would practiced their own forms of Négritude that would take inspirations from various sources, Césaire ‘s Negritude would take inspiration from Jacobnism and would be more for the avocatcy of universal equality as the main goal for Negritude, Senghor’s version was more for the Africans to take pride of their culture while also taking some complientmary traits from European Society. Prior to his presidency, he had negative views on African independence, fearing that the newly formed African nations would devolve into chaos and fragment apart becoming into weaker states. Instead, he dreamed of an African Federation instead. Leon Damas was more radical in his views on Négritude since he saw the movement as a critique of scholarly French assimilation and would actively see both many members of the movement and himself as white Frenchmen because he believed Eurocentric epistemology and methodology were so prevalent in the scholarly world that he couldn’t escape it. He believed that the educational system brainwashed black people into accepting and assimilating into a colonial mindset that would ignore native authors and read French authors instead.

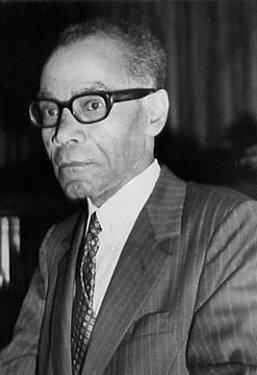

Frantz Fanon

Frantz Fanon was a short-lived member of the movement that was recognized with his most important work, “Black Skin, White Masks” where he explores the black consciousness in a white society. All three members shared a deep frustration with French society’s treatment of black people as la ower form of human and how they felt an injustice from its Racist and colonial practices that they would experience on a daily basis that they needed to expose. His Relationship with Négritude was a temporary one that he believed would be a short-lived movement that would branch and inspiration to new related movements. He believes his interaction was a necessary topic that had relevance to black philosophical thought that he wanted to explore and understand. This would give influence to his works and give way to his ideology, Fanonism

Cited Work(s)

NESBITT, NICK. “Which Radical Enlightenment?: Spinoza, Jacobinism and Black Jacobinism.” In Spinoza Beyond Philosophy, edited by Beth Lord, 149–67. Edinburgh University Press, 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt3fgqs6.14.

HIDDLESTON, JANE, EDMUND SMYTH, and CHARLES FORSDICK. “Léopold Sédar Senghor: Politician and Poet between Hybridity and Solitude.” In Decolonising the Intellectual: Politics, Culture, and Humanism at the End of the French Empire, NED-New edition, 1, 1., 33:38–74. Liverpool University Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt18mbcmv.5.

Rabaka, Reiland. 2015. The Negritude Movement : W. E. B. du Bois, Leon Damas, Aime Cesaire, Leopold Senghor, Frantz Fanon, and the Evolution of an Insurgent Idea. Lanham: Lexington Books/Fortress Academic. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/csus/reader.action?docID=2089522&c=RVBVQg&ppg=278

Thiam, Cheikh. “INTRODUCTION: Decolonialitude: The Brighter Side of Negritude.” Return to the Kingdom of Childhood: Re-Envisioning the Legacy and Philosophical Relevance of Negritude, Ohio State University Press, 2014, pp. 1–11. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1675bxs.4.

Diagne, Souleymane Bachir. “Negritude, Universalism, and Socialism.” Symposium: Canadian Journal of Continental Philosophy / Revue Canadienne de Philosophie Continentale 26, no. 1/2 (December 2022): 213–23. doi:10.5840/symposium2022261/211.

Müller, Ernst Wilhelm. “L’Etudiant Noir, Négritude et Racisme. Critique d’une Critique.” Anthropos, vol. 91, no. 1/3, 1996, pp. 5–18. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40465269. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

Laurence, Proteau, “CÉSAIRE notice, Aimé.”, Maitron, October 25, 2008,

https://maitron.fr/spip.php?article19180.

“L’Étudiant noir : journal de l’Association des étudiants martiniquais en France, March 1, 1935”, BnF Gallica, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9785762s#