By See Vang

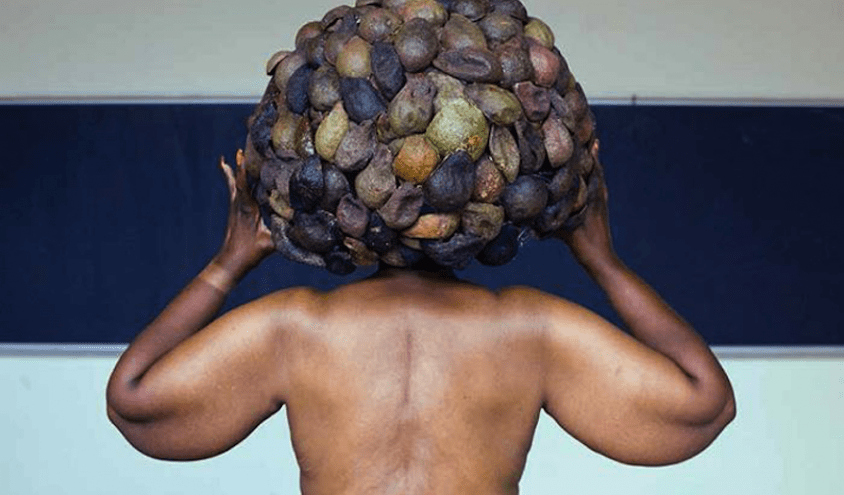

The term “Black female body” refers not only to the physical form of Black women, but to a historically constructed and symbolically charged space that reflects centuries of social control, resistance, survival, and transformation. It is a site where race, gender, power, and culture intersect—a body that has been simultaneously hyper-visible and invisibilized, controlled and liberated, demonized, and celebrated (hooks). In the Pan-African perspective, the Black female body holds deep significance, representing the convergence of colonization, gendered violence, spiritual resilience, and cultural continuity. This essay explores the evolution of how the Black female body has been perceived, regulated, resisted, and ultimately reclaimed, drawing from historical injustices, political movements, and modern cultural expressions. Through this lens, we can better understand how the body serves as a terrain of both oppression and empowerment across the African diaspora.

From the earliest moments of the transatlantic slave trade, the Black woman’s body was rendered a commodity—an object for labor, reproduction, and exploitation. Enslaved African women were forced into a dual role as workers in the fields and as reproducers of more enslaved labor. Their fertility was not a private or sacred matter, but a source of profit. Beyond the plantation, Black women were subjected to horrific medical experimentation. The case of Saartjie Baartman, exhibited in public shows across Europe in the 19th century as the “Hottentot Venus,” illustrates the exoticization and dehumanization of African women’s bodies under colonial gazes (hooks). Her body was not just observed—it was dissected, both literally and figuratively, in the service of so-called “racial science” that justified white supremacy.

Medical apartheid also targeted Black women in the U.S. In the 19th century, physician J. Marion Sims, frequently referred to as the “father of modern gynecology,” conducted experiments on enslaved Black women without anesthesia (Sims). These women, whose names were rarely recorded, became test subjects in a medical system that viewed their pain as negligible (Roberts). This legacy of exploitation has echoed across time, contributing to modern-day mistrust between Black women and healthcare institutions (Pumphrey).

Despite this legacy of violence and control, Black women have long used their bodies as instruments of resistance and resilience. African and diasporic history is filled with figures who fought against colonialism and enslavement. Queen Nzinga of Ndongo, who led armed resistance against the Portuguese, and Nanny of the Maroons in Jamaica, who led enslaved Africans to freedom in the mountains, not only used political strategy but the strength of their physical presence as revolutionary tools. Resistance also took form through reclaiming bodily autonomy. Traditional African healing practices, such as midwifery, herbal medicine, and spirit work, empowered women to care for their communities and themselves on their own terms (Collins). These practices survived the Middle Passage and adapted across America, forming a kind of ancestral continuity that centered the Black woman’s body as both healer and vessel of knowledge.

In the 20th century, the body became an overt political symbol. Black women in the Civil Rights and Black Power movements—figures like Angela Davis and Assata Shakur—embodied resistance, often using their appearance, natural hair, and presence to challenge norms (hooks). The Reproductive Justice movement, led by Black women, reframed the struggle over the body not just as the right to abortion, but the right to raise children in safe, healthy environments—a direct critique of the state violence that polices Black motherhood (Pumphrey; Roberts).

Today, the Black woman’s body remains a contested space—both targeted by systems of control and redefined through cultural expression. Issues like medical racism, unequal maternal health outcomes, and body surveillance continue to disproportionately affect Black women. Studies show that Black women in the U.S. are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications compared to white women, highlighting a deeply concerning disparity that reflects both structural inequities and implicit bias in healthcare (Pumphrey).

At the same time, the media landscape is filled with contradictory representations of Black women. On one end are the enduring stereotypes: the hypersexualized jezebel, the asexual mammy, the “strong Black woman” who never breaks (hooks). These images flatten and silence real experiences. Yet on the other end, a wave of Black women artists, activists, and creators are flipping the script. From Lizzo celebrating body positivity and sexual autonomy, to Serena Williams challenging white ideals of athletic femininity, to Megan Thee Stallion reclaiming twerking as a joyful, liberatory act—the body becomes a canvas for power, not shame. Social media platforms, especially, have enabled Black women to curate their own representations, challenge beauty standards, and build digital communities of support. Hashtags like #BlackGirlMagic and #SayHerName highlight both the beauty and the precarity of being a Black woman in the world today (Blay). And scholars like bell hooks, Patricia Hill Collins, and Yaba Blay continue to develop frameworks that center the Black woman’s body not as an afterthought, but as a starting point for understanding race, gender, and power (Collins; Blay; hooks).

Ultimately, the Black female body is not simply a physical entity—it is a living archive of struggle, memory, and transformation, shaped by systems of colonialism, medical exploitation, gendered violence, and cultural resistance. As both a symbol and lived reality, it serves as a powerful lens for analyzing the complex histories and legacies of the African diaspora. While it has been marked by surveillance, violence, and control, it also remains a site of immense power, creativity, and spiritual resilience. To study the Black female body is to study the ongoing reclamation of autonomy, identity, and agency—one that continues to resist erasure and redefines power on Black women’s own terms, in every gesture, movement, and breath.

Works Cited

Blay, Yaba A. One Drop: Shifting the Lens on Race. BLACK print Press, 2013.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of

Empowerment. Routledge, 2000.

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. South End Press, 1992.

Pumphrey, Shelby Ray. “Reclaiming My Body: Black Women and the Fight for Reproductive

Justice.” University of Louisville, 2014.

Roberts, Dorothy E. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty.

Vintage Books, 1997.

Sims, J. Marion. The Story of My Life. D. Appleton and Company, 1884.